The

title of the centre of the American cocaine trade was adopted by

Colombia from Chile in the late 1970’s. Trade was small and it

inhabited a natural home in Medellin, a city already

historically known for its illicit activities. At the time,

there were two people dominating the cocaine trade in Medellin,

Fabio Ochoa sr. and Pablo Escobar. (Anderson, A History of

the Medellin Cartel, 1988)  Fabio Ochoa sr.

already had connections and trading routes used for smuggling

and it was Escobar who persuaded Ochoa in 1978 to start

smuggling the more profitable cocaine. It was in 1981 when the

drug smugglers: Carlos Lehder, Jorge Luis Ochoa and Fabio Ochoa

jr. (sons of Fabio Ochoa sr.) joined Escobar and Ochoa sr. to

create the Medellin Cartel. They soon had extremely slick

operations of smuggling drugs into the USA by employing a vast

number of different professions, from pilots to government

officials. (Chepesiuk, 1999) However

the infamy of the cartel was not due to their methods of drug

smuggling, but because of their ruthlessness and violence. They

did not hesitate to kill anybody that posed a threat to them, or

anyone that stood in their way. Pablo Escobar “is

believed to have ordered the assassinations of Colombian

justice minister, Rodrigo Lara Bonilla, in April 1984 and

American DEA informant, Barry seal, in February 1984”[1].

The wealth of the Medellin Cartel was almost unimaginable.

In 1989, Pablo Escobar had an estimated net worth of $9 billion

and Carlos Lehder’s estimated net worth was $2.7 billion. (Zschoche, 2008)

They lived lives of excess, buying aeroplanes, zoos and

mansions, while also investing in their local community by

building affordable houses and football pitches for the poor.

However it was their extreme use of violence which ultimately

led to their downfall. On 5th February 1987 Carlos

Lehder was captured by the Colombian Police and subsequently

extradited to the USA and sentenced to 135 years in prison.

Later in 1989, Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha was killed and the Ochoa

brothers all turned themselves in to the police. In 1991,

Escobar gave himself into the police and was sent to a private

prison mansion called La Catedral. In this mansion, Escobar

controlled and ran the cartel and was allowed visitors whenever

he wanted. In July 1992 Escobar escaped La Catedral after

threats of moving him to another prison. After his escape from

prison a huge manhunt began, headed by a special Colombian

police force backed by the US army and a group of his enemies

known as Los PEPE’s (People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar). Pablo

Escobar was eventually shot dead on 2nd December

1993, consequently marking an end to the Medellin Cartel.

Fabio Ochoa sr.

already had connections and trading routes used for smuggling

and it was Escobar who persuaded Ochoa in 1978 to start

smuggling the more profitable cocaine. It was in 1981 when the

drug smugglers: Carlos Lehder, Jorge Luis Ochoa and Fabio Ochoa

jr. (sons of Fabio Ochoa sr.) joined Escobar and Ochoa sr. to

create the Medellin Cartel. They soon had extremely slick

operations of smuggling drugs into the USA by employing a vast

number of different professions, from pilots to government

officials. (Chepesiuk, 1999) However

the infamy of the cartel was not due to their methods of drug

smuggling, but because of their ruthlessness and violence. They

did not hesitate to kill anybody that posed a threat to them, or

anyone that stood in their way. Pablo Escobar “is

believed to have ordered the assassinations of Colombian

justice minister, Rodrigo Lara Bonilla, in April 1984 and

American DEA informant, Barry seal, in February 1984”[1].

The wealth of the Medellin Cartel was almost unimaginable.

In 1989, Pablo Escobar had an estimated net worth of $9 billion

and Carlos Lehder’s estimated net worth was $2.7 billion. (Zschoche, 2008)

They lived lives of excess, buying aeroplanes, zoos and

mansions, while also investing in their local community by

building affordable houses and football pitches for the poor.

However it was their extreme use of violence which ultimately

led to their downfall. On 5th February 1987 Carlos

Lehder was captured by the Colombian Police and subsequently

extradited to the USA and sentenced to 135 years in prison.

Later in 1989, Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha was killed and the Ochoa

brothers all turned themselves in to the police. In 1991,

Escobar gave himself into the police and was sent to a private

prison mansion called La Catedral. In this mansion, Escobar

controlled and ran the cartel and was allowed visitors whenever

he wanted. In July 1992 Escobar escaped La Catedral after

threats of moving him to another prison. After his escape from

prison a huge manhunt began, headed by a special Colombian

police force backed by the US army and a group of his enemies

known as Los PEPE’s (People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar). Pablo

Escobar was eventually shot dead on 2nd December

1993, consequently marking an end to the Medellin Cartel.

Cali Cartel

The

Cali Cartel was the main rival in terms of size and power to the

Medellin Cartel. However throughout most of the 1980’s it was

inferior, and only gained superiority after the arrests of the

Medellin Cartel members in the late 1980’s and the death of

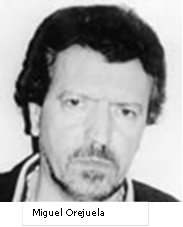

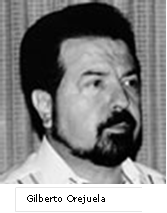

Pablo Escobar in 1993. The main founders of the Cartel were the

brothers Gilberto and Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela, and their

friend Jose Santacruz Londoño.

They started off in the drug trade in the 1970’s in trafficking

marijuana. (Chepesiuk,

1999) In the same manner as the Ochoa’s of

the Medellin Cartel, they decided to progress onto the Cocaine

business due to the lure of increasing profits and higher

prices. In 1975, Hernando Giraldo Soto was sent to New York to

establish trade links in Queens for the Cali Cartel, thus giving

them a power base within the United States. A power base which

could rival the Miami headquarters of the Medellin Cartel. The

cartel kept growing at an exponential rate to the point that "in 1996, it was believed

the Cartel was grossing $7 billion in annual revenue from the

US alone.”[2]

There are two significant ways in which the Cali Cartel

differed from the Medellin Cartel, the first being the more

professional nature of the Cali Cartel, and the second one being

the way the Cali Cartel was organised. The Cali Cartel was much

less inclined to resort to violence than the ruthless Medellin

Cartel. They acted like a legitimate corporation. According to

Robert Bryden, head of the New York DEA, “The

Cali Cartel will kill you if they have to, but they would

rather use a lawyer.”[3]

The

Cali Cartel was the main rival in terms of size and power to the

Medellin Cartel. However throughout most of the 1980’s it was

inferior, and only gained superiority after the arrests of the

Medellin Cartel members in the late 1980’s and the death of

Pablo Escobar in 1993. The main founders of the Cartel were the

brothers Gilberto and Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela, and their

friend Jose Santacruz Londoño.

They started off in the drug trade in the 1970’s in trafficking

marijuana. (Chepesiuk,

1999) In the same manner as the Ochoa’s of

the Medellin Cartel, they decided to progress onto the Cocaine

business due to the lure of increasing profits and higher

prices. In 1975, Hernando Giraldo Soto was sent to New York to

establish trade links in Queens for the Cali Cartel, thus giving

them a power base within the United States. A power base which

could rival the Miami headquarters of the Medellin Cartel. The

cartel kept growing at an exponential rate to the point that "in 1996, it was believed

the Cartel was grossing $7 billion in annual revenue from the

US alone.”[2]

There are two significant ways in which the Cali Cartel

differed from the Medellin Cartel, the first being the more

professional nature of the Cali Cartel, and the second one being

the way the Cali Cartel was organised. The Cali Cartel was much

less inclined to resort to violence than the ruthless Medellin

Cartel. They acted like a legitimate corporation. According to

Robert Bryden, head of the New York DEA, “The

Cali Cartel will kill you if they have to, but they would

rather use a lawyer.”[3] They even owned many legitimate businesses like apartment

blocks, car dealerships, a large drug store chain, and of

course, the football team, América de Cali. This is summarised

well by Chepesiuk, claiming that "[Cali

cartel co-founder Gilberto Rodriguez] became known as the

“Chess Player” for his ruthless and calculating approach to

the drug business. … The Rodriguez brothers … controlled

Cali in the way that feudal barons once ruled medieval

estates. … Buy Colombia, rather than terrorize it, became

their guiding philosophy. … The cartel built dozens of

high-rise offices and apartment buildings as a way of

laundering their money. The Cali skyline changed, and

thousands of jobs were created. Their money permeated the

city’s economy, and the natives became addicted to laundered

cash and conspicuous consumption."[4]

It was this reluctance to

violence which allowed the Cali Cartel to flourish slightly

under the radar, while the Medellin Cartel constantly made

violent headlines all across the globe. The Cali Cartel also

had a very unique structure and organisation. They were

organised into individual cells which were responsible for

different sections, from narco-trafficking to finance. Each

cell was highly responsible for its own activity. This is

contrasting to the highly centralised control of the Medellin

Cartel by Escobar. (Washington,

1991)

However the Cali Cartel came to an end in the late 1990’s when

the majority of the leaders of the Cartel, including the

Orejuela brothers, were captured by the Colombian police backed

by the DEA and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Along with the Medellin Cartel, the Cali Cartel was one

of the most powerful criminal organisations in history.

According to the DEA, in 1991, the Cali Cartel “produces

70% of the coke reaching the U.S. today, according to the DEA,

and 90% of the drug sold in Europe.”[5]

They even owned many legitimate businesses like apartment

blocks, car dealerships, a large drug store chain, and of

course, the football team, América de Cali. This is summarised

well by Chepesiuk, claiming that "[Cali

cartel co-founder Gilberto Rodriguez] became known as the

“Chess Player” for his ruthless and calculating approach to

the drug business. … The Rodriguez brothers … controlled

Cali in the way that feudal barons once ruled medieval

estates. … Buy Colombia, rather than terrorize it, became

their guiding philosophy. … The cartel built dozens of

high-rise offices and apartment buildings as a way of

laundering their money. The Cali skyline changed, and

thousands of jobs were created. Their money permeated the

city’s economy, and the natives became addicted to laundered

cash and conspicuous consumption."[4]

It was this reluctance to

violence which allowed the Cali Cartel to flourish slightly

under the radar, while the Medellin Cartel constantly made

violent headlines all across the globe. The Cali Cartel also

had a very unique structure and organisation. They were

organised into individual cells which were responsible for

different sections, from narco-trafficking to finance. Each

cell was highly responsible for its own activity. This is

contrasting to the highly centralised control of the Medellin

Cartel by Escobar. (Washington,

1991)

However the Cali Cartel came to an end in the late 1990’s when

the majority of the leaders of the Cartel, including the

Orejuela brothers, were captured by the Colombian police backed

by the DEA and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Along with the Medellin Cartel, the Cali Cartel was one

of the most powerful criminal organisations in history.

According to the DEA, in 1991, the Cali Cartel “produces

70% of the coke reaching the U.S. today, according to the DEA,

and 90% of the drug sold in Europe.”[5]

[1] Jack Anderson, A history of the Medellin Cartel, The Byron Times, 1988

http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=799&dat=19880824&id=ufY0AAAAIBAJ&sjid=JYgDAAAAIBAJ&pg=3197,4841722

[2] Kevin Fedarko, OUTWITTING CALI'S PROFESSOR MORIARTY, TIME, 1995, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,983173,00.html

[3] Ron Chepesiuk, The War on Drugs An International Encyclopedia, 2001.

[4] Ron Chepesiuk, Drug Lords: The Rise and Fall of the Cali Cartel, 2005

[5] Elaine Shannon Washington, Cover Stories: New Kings of Coke, TIME (24/06/1991)